There have been some stellar intellectual influences on my work. While the list is long, some of these figures have been integral to the journey.

Ashis Nandy

I recall reading Ashis Nandy’s Intimate Enemy and Traditions, Tyranny, and Utopias in my undergraduate years at St.Joseph’s College in Bangalore. We had a wall magazine at the College which encouraged reviews and short articles that were featured on one of the notice boards. I was keen to review Traditions, Tyranny and Utopias and was glad when it eventually made it to the chosen destination. I loved Nandy’s work for its provocations as also for its beautiful crafting. I learnt many things about the colonial encounter from Nandy’s work and decided that if I eventually did get to Delhi for my higher studies, I would meet with him in person. Soon after I joined Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) for a postgraduate degree. I set up an appointment with Nandy at Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) on Rajpur road and visited him in his office.

In my final undergraduate year, I had written an essay titled ‘Etiology Unknown’ and was keen to share it with Nandy and elicit his reaction. Nandy was absolutely generous in first granting an obscure Masters student from JNU an appointment and subsequently to read the piece and share his thoughts on it with me. He also told me that he had shared it with his wife Uma Nandy who apparently also appreciated the piece. I have always admired Uma Nandy for her candour and warmth. She continues to generously invite Vineeta and me home whenever we meet. To me, at that stage of my nascent socialization in the world of the social sciences, meeting Nandy was an important rite of passage and I was delighted when it actually transpired. What I once dreamed of came true.

During my doctoral years, Nandy was also very supportive of my intent to pursue the ‘personal philosophy of international law’ of Judge Christopher Gregory Weeramantry as a part of my doctoral inquiry. I was then focused on the July 1996 Advisory Opinion of the International Court of Justice on the legality of the threat or use of nuclear weapons. Judge Weeramantry was the Vice-President at the ICJ in 1996 and also filed a Dissenting Opinion in response to the dispositif of the Advisory Opinion. Eventually, the chapter on Weeramantry turned out to be a wonderful opportunity to think about questions relating to historical location, politics and international law. It was my first attempt to straddle the world of politics and international law and I much enjoyed researching and writing the piece.

These interests have endured and Nandy plays no small part in it. Nandy read my chapter in my doctoral thesis with great interest, inspired as it was from his own pioneering treatment of Radhabinod Pal’s ‘personal philosophy’ of law in the light of the Tokyo Trials and his eclectic social background. Over the years, I have followed the work of Nandy with interest and have also enjoyed meeting him in person whenever the opportunity arose.

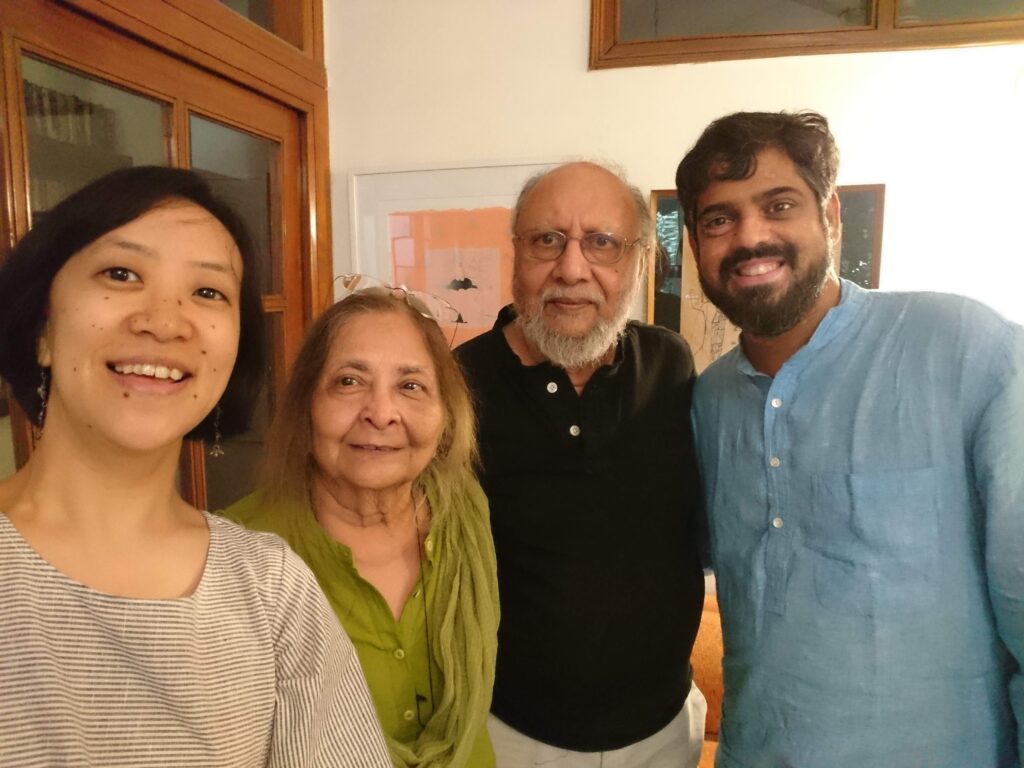

The picture reveals a fine memory from a visit to his house, with my wife Vineeta. It was a lovely afternoon with the Nandys, both characteristically warm and always taking interest in the best sense of the term in the lives of others. My first impressions of Nandy have lasted through all these years. His unassuming nature, warmth and erudition carried lightly on the sleeve have been his distinctive hallmarks.

Kanti Bajpai

I have been incredibly fortunate to have had Professor Kanti Bajpai as my academic mentor for over three decades now. My first memory of him is in a classroom at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) in the Monsoon Semester of 1994 having enrolled for a Master’s Programme in Politics (with a specialisation in International Relations) at the School of International Studies.

Kanti offered us a course titled Theory of International Relations which till this day ranks among the finest courses I have credited. It introduced us to the many worlds of theory, exposed us to both successful and unsuccessful experiments in theorizing along with an enticing intellectual history of key theoretical strands in international relations. It raised a number of worthwhile questions about the provenance of theory (a largely Western dominated lineage then and now), the ‘resistance to theory’ in the Global South (including India), what counted as ‘good theory’ and the vital need to rehabilitate bodies of international thought in the global South to eventually contribute to world theorizing and theorizing about the world. I owe my continued love for theory to Kanti’s lively introduction and his illumination of the possibilities that sound theorizing promises.

Even if I had any initial inclinations to consider the foreign service as a career choice, the exposure to Kanti’s classes made me aspire for a life of the mind – the world Kanti himself was immersed in and an exemplar to boot. Interpreting world politics (one of the titles of his books) as a vocation appeared worthwhile to me now considering the intellectual challenges it posed and the tangible and intangible rewards of sustained academic reflection. On the first day in class, Kanti carried a bundle of books, old and new, along with a detailed copy of the course design. His generosity shone through from the beginning – he lent his books with ease, welcomed us with care and warmth to the rich world of eclectic ideas and intellectual inheritances, taught us how to write academic prose and made us work hard. It was a sheer joy. I was sold early. The quality of his mind combined with his rigour held us in awe then and his sheen has not faded one bit after all these years.

Kanti went on to supervise my M.Phil dissertation and doctoral thesis. The latter exercise culminated in my first book titled Banning the Bomb: The Politics of Norm Creation in 2007. During the course of my doctoral research, Kanti also introduced me to the world of academic publishing. We co-edited two volumes on International Relations in India which were both published in 2005. My first publications were both in 2003, a piece I wrote for Seminar that year, while also contributing a chapter in a book edited by M.V.Ramana and Rammanohar Reddy titled Prisoners of the Nuclear Dream. I owe him a serious intellectual debt.

It was Kanti who introduced my doctoral focus and work to Rammanohar Reddy and M.V.Ramana which led to the invitation to contribute to this exciting book project. I was delighted to be in a collection which featured some prominent scholars including Amartya Sen and Amulya Reddy, the former whose credentials need no elaboration and the latter an academic and scientist of distinguished standing at the Indian Institute of Science. Kanti and I have subsequently co-edited a more recent volume titled India, the West and International Order published in 2019. We continue to meet (as we did here in the picture in May 2024 in Singapore) and collaborate whenever an opportunity arises and our schedules permit. I have turned to him for academic advice over the years and he has always been unfailingly generous with his counsel and time. Kanti’s own scholarship over the years has demonstrated how to research and write with erudition and precision, how to create compelling typologies and straddle the worlds of academia and policy with consummate ease. I continue learning from my mentor and dear friend now.

B.S.Chimni

Professor Chimni has been and continues to be a unique academic influence on me in many ways. I initially met him when my doctoral advisor Professor Kanti Bajpai asked me to consult him on my developing area of doctoral research interest, i.e. the legality of the threat or use of nuclear weapons. Chimni listened to me patiently and offered some wonderful clues on how to proceed. This also paved the way for now close to three decades of sustained conversations about the imbrication of international relations with international law and a lot else. It is to the credit of my alma, JNU that I met the two hugely influential figures on my subsequent academic trajectory, Professor Bajpai and Professor Chimni in the same institutional setting. Chimni also kindly consented to write a foreword to my book, Banning the Bomb: The Politics of Norm Creation. It meant a great deal to a younger scholar like me finding his feet in the academia. He was magnanimous in his endorsal while gesturing to further possibilities for building on the intellectual project.

If I were to sift the specific influences of Chimni on me, they would register as the following. First, from Chimni, I developed an understanding of our distinct positionality when it came to the study of International Relations. The position of the underdog, not as victim but of a distinct cluster of agential political subjectivities. The third world, the global South whatever we may wish to call it was a space that needed empathy and care to understand. IR was different in the margins and could not merely be a pale shadow of what percolated to us from the Anglo-American academia. After all, the international law department pioneered a third world approach to international law (TWAIL). From Chimni, I came to appreciate the need to understand India and its place in the world on our own terms unmediated only by what Saikat Majumdar in his book, The Amateur refers to as the ‘ideology and infrastructure of imperialism’, i.e. Enlightenment social science.

Second, it was Chimni who paved the way for centering my attention on disciplinary histories hidden from view. This was well before it became fashionable to do so. The histories of international law were going through some fundamental revisionism and IR was trailing behind. I began to understand the need to pay more attention in this area as a consequence of our many conversations in this space. As I move towards the completion of my book in this area, I owe a special debt to Chimni and the many long walks and conversations we have had over the years particularly in this niche.

Third, Chimni also demonstrated through his own scholarship that you could be homespun and hold your own internationally amongst the best. There is scarcely a form of recognition in international law scholarship that has eluded Chimni. It is not surprising considering his originality, hardwork and patience over the years. His recognition internationally has far surpassed his recognition at home in India. The recognition at home has come in dribbles and only after his recognition abroad. This gives us a sense of how we still have a long way to go in terms of fairly acknowledging scholarship in India. However, on a more positive note, Chimni (still prolific in his academic output) serves as a wonderful inspiration to other homespun scholars like me. If you could accomplish all of what Chimni has notwithstanding the many constraints that faced a prior generation of scholars, there is no reason why a generation better privileged in terms of access to a variety of world resources today cannot aspire for these standards of excellence.

Four, from Chimni I learnt the need for a greater appreciation of the vitality of material and political economy influences in shaping legal and political outcomes. He is of the view that fundamental economic orientations exercised an often unaccounted for influence that was oftentimes not studied closely enough. This is undoubtedly inspired by his immersion in sound Marxist critique without being doctrinaire. What is refreshing in his approach was his willingness to apply it with care across diverse issue areas (refugee questions, international trade formulations in law, foreign policy and in the working of international organizations)

Finally, Chimni also taught me to place fundamental political questions at the heart of any inquiry. This included any attempt to disentangle the liminal threads of international relations and international law. His lament was that many journal articles which appeared competent and stylized left one feeling bored and cold after reading. This could be attributed to their unwillingness to address any fundamental political question. Trivia often trumped more substantive political inquiries and this he urged me needed to be avoided like the plague.

The picture is from a meeting in 2010 of Chimni, Judge Christopher Gregory Weeramantry who was a former Vice President of the International Court of Justice and me. Weeramantry himself embodied the best of TWAIL spunk having dissented in the July 1996 Advisory Opinion but also having contributed immensely to shaping a distinctly global South perspective on a whole range of international developments by no means confined only to the nuclear disarmament arena.

Rupamanjari Ghosh

Professor Rupamanjari Ghosh would easily count amongst the best Vice Chancellors, I have seen in India. She is a physicist by training but her years in Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) also familiarized her with what a life in the social sciences entailed. She was political in the best sense of the term, protecting faculty interests and priorities in an increasingly neo-liberal academia. I had known her in JNU when she approached me to join the JNU Teachers Association (JNUTA) which I did although I declined contesting elections for any office in the same body.

Many years later, Rupamanjari invited me to join Shiv Nadar University (SNU) which she was now helming to help build a Department of International Relations. Having known Rupamanjari from earlier and with great admiration for her panache, I was open to the professional opportunity. I was also at a stage in my professional life when I was looking for a change having spent close to a decade and a half in public universities (including the premier JNU as a faculty member). I would have been wary of a private university, given my JNU intuitions, but I felt confident reposing my faith in the leadership of Rupamanjari at SNU.

I took a calculated risk, leaving a well-established JNU for a new and somewhat obscure private university at that stage. Thanks to Rupamanjari’s leadership, SNU is now designated the Shiv Nadar Institution of Eminence (SNIoE) and belongs to an exclusive handful of universities across India which have received this special status. It was undoubtedly the most rewarding move of my career intellectually. Rupamanjari had made it mandatory for me to join as Head of Department and I took on this responsibility with a mix of trepidation and a desire to step up to the plate.

This must be placed on record. There is no institution in India till date with the exception of SNIoE that has given me the space and academic freedom to build such a fine Department of International Relations. Along with a group of talented colleagues, we worked (and continue to do so) relentlessly in pursuit of this objective. From modest beginnings, today we are doing well in terms of teaching, research and impact in relevant arenas. I have no doubt that much of this was made possible by the intellectual stewardship of Rupamanjari. During these years, we launched a four year undergraduate IR Major research degree in International Relations and a doctoral program in International Relations and Governance Studies. We have an excellent crop today of undergraduates and doctoral research scholars. There is still much to be done but it only demonstrates what able leadership at the highest academic rungs of the university can possibly enable.

Rupamanjari is an excellent blend of formal and informal in her professional interactions. There is much I continue to learn from her style and mode of being in the world. A really fine academic who held her own in an academic world still dominated by men. She could resolve departmental dilemmas over a cup of coffee and inspire you to reach for the stars academically speaking. Her rare combination of academic and administrative finesse were bound to leave an imprint on anybody she met. I am delighted I had that opportunity and I sincerely hope that the imprint of fine attributes stays with me for good. The picture is from a warm lunch meeting with Rupamanjari after she had left SNIoE. Vineeta and I particularly enjoyed this get together.

All your memories are beautiful over decades with encouraging mentors over the years..

The textual representation of memories and the hard work done by the design team is wonderful..

Best regards

Amrit N